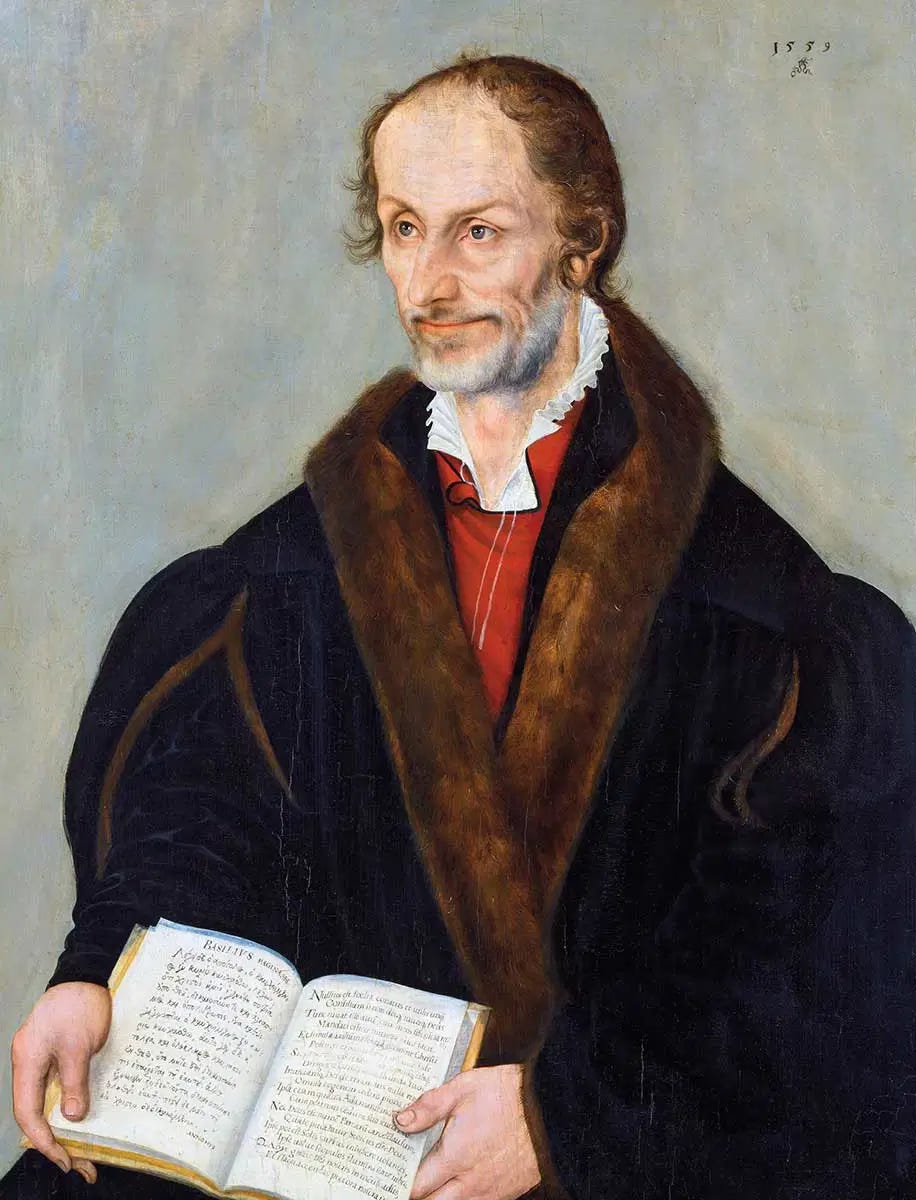

I have been re-reading Philipp Melanchthon’s 1521 Loci Communes, and was struck by his repeated use of the term “conversance.” In his introduction to the Communes, he communicates his desire that all Christians “be conversant with the Scriptures.” Though this is not a phrase with which I am entirely familiar in the broader corpus of Lutheran systematics, I appreciate Melanchthon’s sentimentality concerning the need to be intimately and intentionally familiar with and knowledgeable in the Scriptures.

The word conversant is a variant of the word “converse,” and is taken from the Old French present participial form of the word converser. The original sense was “habitually spending time in a particular place or with a particular person.” It was eventually used to denote “familiarity with or knowledgeability about something.” Given its historical usage, however, I posit that it goes beyond a general familiarity, but represents an intricate and intimate recognizance.

Melanchthon summarizes this scriptural recognizance by emphasizing the centrality of the Scriptures in Christian doctrine. Specifically, Melanchthon notes that Holy Scripture is God’s revelation to mankind. He writes, “For since the Godhead has expressed its most complete image in them, it cannot from any other source be more surely or correctly known.”1 The only medium by which we can truly know God is Holy Scripture. Natural knowledge of God certainly exists, yet it alone cannot point us to the identity and nature of our Creator. Scripture alone tells us who our God is and what our God has done.

This knowledge is the foundation of the Christian faith. Apart from the Scriptures, faith cannot stand. Melanchthon contends that “faith is nothing other than reliance upon the divine mercy promised in Christ,”2 and claims that “faith is the constant ascent to every word of God.”3 Melanchthon has therefore established that the Word of God, His self-revelation to mankind, is the sure foundation of faith.

“He is mistaken who seeks the form of Christianity in any other source than the Canonical Scriptures.”

—Philipp Melanchthon

Conversance with the Scriptures is not mere familiarity. All things must be characterized by Scripture. It is the source of doctrine and the foundation of Christian faith. It is the rhythm and pattern of the Christian life. Our conduct, character, and daily pattern must be normed and shaped by Holy Scripture. Such is the essence of Christianity. To be a Christian is to be shaped and molded by God’s Word—that we follow God’s Law, imitate Christ, and live according to “every word that proceeds from the mouth of God” (Deut. 8:3).

Thus, conversance with the Scriptures is marvelously demonstrated by the holy liturgy. The Church’s liturgical traditions and practices originate from Scripture. Our liturgical heritage follows the biblical pattern of worship illustrated throughout both the Old and New Testaments. The systematic organization of our liturgy—and the liturgy’s bearing on our doctrine—is not unique to the post-Pentecost Christian Church. It is ordained by God in eternity as the means by which His Word is proclaimed, His promises are taught, and His gifts of grace are administered.

The Church’s liturgical pattern, for example, closely mirrors the pattern of worship of the Israelites in the Old Testament. God’s prescriptive liturgical commands were not meant to restrict the Israelites’ worship. Rather, these commands spiritually enriched the Israelites by feeding them with God’s Word and pointing them to God’s grace, the means of which would one day be secured by Christ through His Passion and Resurrection. Following the descent of the Holy Spirit, the Christian Church recognized the spiritual and ceremonial value in worshipping in an organized manner. St. Paul commends as much in 1 Corinthians 14:40 when he says, “Let all things be done decently and in order.”

All liturgy celebrated in the Church—at least those elements that conform to the historical pattern and doctrinal standards of the true Church—is drawn solely from Scripture. As the liturgical prescriptions God declared for His people of old are revealed in sacred Scripture, so also therefrom is His desire that we receive His Word and Sacraments revealed. Accordingly, the liturgy’s scriptural foundation is seen not only in its structure, but also in its content. The words of the liturgy are taken from Scripture; the liturgy is not broadly “rooted” in Scripture, but fully conformed to and characterized by it.

The liturgy is the active, faithful practice of the Scriptural conversance to which Melanchthon exhorts all Christians. We are to be in every way familiar with and intimately conformed by God’s Word. We are to be fed with His Word and Sacraments by virtue of His command. We are to faithfully and frequently receive His grace “in good order.” Were we to seek the gifts of the Christian faith apart from this scriptural pattern and biblical foundation, we would certainly fail. We would find nothing but despair. God’s gifts—indeed, His Means of Grace—are not only good and gracious in themselves, but constitute the scriptural conversance for which Melanchthon contends—and for which we ought to strive.

Insistence that the liturgy be observed in the Church is grounded in the necessity for Christians to be conversant with the Scriptures. The exhortation to observe the holy liturgy is an exhortation to be intimately and personally conversant with God’s inspired and inerrant Word—to follow God’s Law, imitate Christ, and live according to God’s every word. In following the Church’s historical liturgical pattern, Christians become familiar with and conform to God’s Word.

We take God’s Word to heart through repetition, chanting, and singing. We learn Scripture not only by memory but also take it to heart when we observe the liturgy. For the liturgy teaches, confesses, and corrects. It serves as a tool by which Christians are admonished by God’s Word, brought to receive God’s precious gifts, and bestowed everlasting life in Jesus’ name. These are gifts God loves to give. Let us therefore gladly and faithfully receive them; such is our hope and joy. It is the faithful conversance with the Scriptures by which we live. It is the Christian life.

Philipp Melanchthon, The Loci Communes of Philipp Melanchthon, tr. Charles Leander Hill (Boston: Meador Publishing Company, 1944): 64.

Ibid., 177.

Ibid., 176.

Maybe a translation difficulty