Ask a Roman Catholic how many Sacraments there are, and he tells you seven. Ask a modern Lutheran, and he tells you two. Ask a Baptist, and he tells you, “We have two, but they’re called church ordinances.” Ask a Pentecostal, and he tells you, “Ew! No! Sacramentalism is just sacrilegious!” Ask a Mormon… Well, don’t, because they are not Christian.

I’m a Lutheran, but I say three.

For many this is simply a quirky view. It is also a particularly disputed view in the Lutheran Church, and it stems from two main issues: the precise definition of “sacrament” and a misunderstanding of how confession and absolution fulfills that definition. The definition of sacrament can vary from denomination to denomination. Historically, the Lutheran Church has defined a sacrament as a rite (a collection of liturgies or a sacred ceremony which is given by God) commanded by God to which His promise of grace is attached. Conventional Protestantism also attaches a physical attribute, though this is something the Lutheran Confessions notably leave out. Baptism and the Holy Eucharist are universally considered sacraments (or ordinances for some Protestants) because they fit the outlined definition in the Lutheran Confessions but also have physical attributes (Baptism in the water and the Eucharist through the Body and Blood of Christ). Confession and absolution does not conventionally fit this definition because it lacks an obvious physical attribute

It is important to note, however, that confession and absolution is a means by which Christ delivers His grace to His people (the absolution is quite literally His forgiveness being given to us through His pastors). Not to mention, it does also have an often-overlooked physical attribute--or perhaps a few.

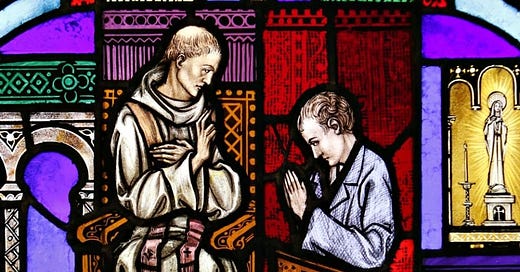

Historically, the Roman Catholic Church view of confession and absolution differs slightly from the Lutheran understanding. Most people have heard of the confession booths used in the Catholic Church. These are physical spaces where confession and absolution chiefly takes place. The priest sits on one side of the booth while the penitent sits on the other, often separated by a latticed opening so that the priest and the penitent cannot see each other. This serves several purposes, namely so that the penitent is reminded that it is not the priest’s forgiveness but God’s forgiveness being spoken. This comes out particularly in the Lutheran Service Book's rite of corporate confession and absolution, meant for use between a pastor and more than one penitent, when the pastor says, "Do you believe that the forgiveness I speak is not my forgiveness but God's?" to which the congregation replies, "Yes." Additionally, a confessional booth hides the penitent from the priest so that he is not tempted to judge the penitent for the sins to which they are confessing. The idea of confessional booths, also known as confessionals, would be helpful for Lutherans for these reasons, mainly the former, but they are unfortunately hard to find in Lutheran churches today. Some confessionals may have a removable curtain, so that the penitent may choose between simply receiving the sacrament of confession and absolution or additionally conversing with the priest/pastor. for additional counseling. This would especially benefit to the Lutheran Church today.

Besides this, Lutherans also observe another physical attribute in the Sacrament of Confession and Absolution when the pastor lays his hands on the penitent while pronouncing the words of absolution. This is a common rubric in confession and absolution, especially since Lutheran churches have lacked confessional booths. Though the pastor laying his hands on the penitent is not what truly transmits absolution, it hearkens back to the New Testament’s indication that imposition of hands signified a blessing and an act of healing. In the same way, confession and absolution is a blessing to God’s people, as they are absolved from their sins and receive God’s forgiveness. This is a parallel image to healing. The Sacraments are given to us as a means of healing from the fleshly disease of sin. God’s heavenly restoration is given to us in His sacramental blessings. This is why all of the Sacraments, including confession and absolution, are so important. Inconveniently, the rubric of touching the head of the penitent is incompatible with the use of confessional booths (unless there is an opening which is used during the absolution), and therefore churches would have to decide between these two traditions.

But perhaps more importantly, the penitent hears the words of absolution. Christ’s words of forgiveness spoken through the pastor are heard by the penitent and received by faith. Christ’s forgiveness was first spoken to us, and every time we hear the words of absolution, we are hearing the completion of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross for the forgiveness of sins. Regardless of where confession takes place, it is only once the words of absolution, that is, God's forgiveness, are spoken that the penitent is forgiven of his sins. The words are spoken, and God's forgiveness is given to the penitent.

Luther’s Large Catechism lists confession and absolution as “the third sacrament,” and the Apology of Augsburg Confession lists confession and absolution in its definition of “sacrament.” The Apology of the Augsburg Confession also states that “Absolution can properly be called a Sacrament of repentance, as even the more learned scholastic theologians say.” Beyond its sacramental definition, the Augsburg Confession also says of confession and absolution: “Our churches teach that private Absolution should be retained in our churches, although listing all sins is not necessary for Confession” (XI 1), and “The Church ought to impart Absolution to those who return to repentance […] repentance consists of two parts. One part is contrition, that is, terrors striking the conscience through the knowledge of sin. The other part is faith, which is born of the Gospel or the Absolution and believes that for Christ’s sake, sins are forgiven” (XII 2-5). This was a break from the Roman Catholic understanding of repentance, which held that there was a third part of repentance called “satisfaction of deeds.” The Apology defends this position by saying that Christ’s quote in Matthew 11:28 (“Come to Me, all who labor…”) signifies the “contrition, anxiety, and terrors of sin and death” (XIIA 44). The Apology states further, “To “come to” Christ is to believe that sins are forgiven for Christ’s sake […] In Mark 1:15, Christ says, “Repent and believe in the Gospel.” In the first clause He convicts us of sins, and in the second He comforts us and shows the forgiveness of sins” (XIIA 44-45).

Does it really matter what we say is a sacrament? The answer is yes, it does. For one, it fits the general (and accepted) definition of a sacrament, and so its exclusion from the list is unnecessary. But more importantly, a sacramental understanding of confession and absolution reminds us of its importance. It cements the idea that absolution is one of the chief gifts of Christ. It was a direct result of His death on the cross. And without His forgiveness (absolution), we cannot inherit the kingdom of heaven. Confession and absolution as a sacrament also reminds the Church that God requires confession. He requires us to repent and be contrite. While we understand the Holy Eucharist to be His Means of Grace, wherein He gives us mercy and grace, confession and absolution is quite literally God’s forgiveness and declaration that we are made righteous before Him through Christ.

Christians, even Lutherans, are often afraid of confession and absolution, regardless of whether it is considered a sacrament or not, because humans seldom enjoy telling others of their weakness. There is also a fear that the pastor, if he is to hear specific sins, might judge the penitent or think less of him, or even worse, use the knowledge of the penitent's sin against him. When all is said and done, humans naturally prefer to hide their shortcomings. Yet this is unhelpful for the Christian. A Christian receives much comfort and joy knowing that his individual sins, especially those which weigh heavily on his heart, are forgiven, and he can finally hear that he is absolved of them by God's grace and mercy. But a penitent does not even have to list his sins at all during confession and absolution. In the LSB, rightfully so, there is an optional rubric to list sins that are specifically weighing on the penitent's heart. A penitent, if he chooses, can simply confess his sins generally and receive the same absolution; God's forgiveness does not hinge on whether or not we list each individual sin. So long as the heart is contrite, the soul faithful, and the conscience stricken, God's forgiveness is sufficient.

If the sacraments are God’s Means of Grace, are commanded by God, and are rites of the Church, then it is nonsensical to deny the very sacrament wherein God’s grace and forgiveness is directly pronounced to His people. Sacraments have historically been understood to be the most important elements of corporate worship life. And so confession and absolution is, as we say to God, “Be merciful to me, a sinner!” and he says to us, “Go forth, my child, forgiven and redeemed.”

*Article image taken from Gottesdienst, from their article on restoring confession and absolution in the LCMS. I encourage you to read the article by clicking this link.

I agree!